Introduction

The aftermath of the 9/11 attacks illustrated the value of efficient network user experiences that rely on Internet-style connectivity. This decentralized architecture enables people to use messaging and email to communicate directly as substitutes for phone calls when telephone networks are congested or unavailable.

For a 9/11 commemorative event held in 2009 at Tufts University in Boston, I was invited to give a colloquium for an audience of Computer Science and Engineering students, faculty and the broader Tufts community. As a former cell phone designer and seasoned user experience practitioner, I was asked to speak on mobile device communications and how cellular technology had changed since the attacks on the World Trade Center towers on 9/11/2001.

While mulling over what might make a good presentation topic, I started thinking about the quality of networked user experiences under catastrophic conditions.

In planning my presentation, I considered the impact of network infrastructure, cellular network access and how people in and around the towers in New York City on 9/11 would have experienced limited or no connectivity via their cell phones because of network congestion. From a device hardware perspective, I thought about the impact of battery life on their experiences. I thought about how their loved ones relied on centrally broadcast information – television news and news websites – to learn about the situation at ground zero in New York City.

From an end-user communication perspective, I had my own experiences in Boston to draw upon. Soon after seeing the reports on CNN of the planes hitting the towers, I made a frantic trip to gather my son at preschool and bring him home safely. I had no idea how the rest of the day would unfold across the US, and as such wanted my son to be at home with me. I remember that the sky in Boston that morning was very clear and a brilliant blue that I have never forgotten. I can recall my desperate attempts to reach colleagues – via cell phone and email – those I knew who were working in or close to the towers in New York City that day. But my calls were not getting through.

By 9:30 am in Boston, I started to call friends on the west coast to warn them, even though it was 6:30 am Pacific time.

To prepare for my talk, I had a lot to consider.

Comparing networked experiences after 2001

After a few revisions, I delivered my colloquium talk during September of 2009 with the title “Crowds and the Cloud: contemporary networked user experiences”. My presentation contrasted an end-user’s 2001 ground zero network user experience with the experience of the same catastrophic event occurring eight years later, in 2009.

I envisioned what a catastrophic event in 2009 would look like from a network experience perspective given improved network connectivity, the availability of location-aware devices and more accessible means for sharing content data such as status, images and video.

Walking through a scenario of a young professional in New York City named Max starting his day early on September 11, 2001, I detailed his typical networked experiences before, during and after the 9/11 attacks. I compared and contrasted Max’s network experience over the day analyzed across three dimensions:

- Content consumption

- Communication capabilities

- Creation and sharing of content

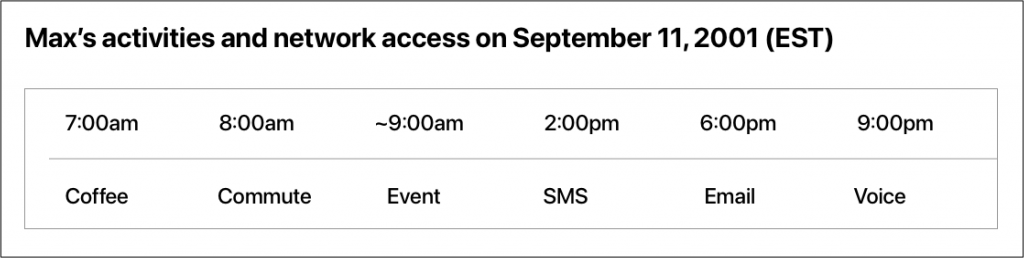

To help explain the scenario, I showed a simple timeline visualization of Max’s day and his network activities (shown below).

Max would spend his morning commute reading a newspaper since there would be no network connectivity in the subway. After the first attack just before 9 am EST, Max’s cell phone would have limited or no data service, leaving him unable to easily communicate his location and status to his friends, family and colleagues.

Although at the time, Max could still acquire content at ground zero – i.e. use his cell phone camera to take photos or videos – it would have been challenging or impossible for him to share any data because of cellular network congestion that morning. It would have also been difficult for Max to find up-to-date news sources because of a lack of network connectivity.

After the day proceeded on 9/11, cellular phone networks in Manhattan were severely congested, so e-mail and instant messages served as substitutes for telephone calls. Max could communicate by sending text messages and email, and it would only be later that night, after leaving Manhattan on foot, that Max could make a voice call to his family.

The remainder of my talk contrasted the catastrophic conditions on 9/11 in 2001 with more “fault-tolerant” networked user experiences available eight years later in 2009. For example, eight years after 9/11, people could access other network options if the cellular network was not available for making calls – limited public WiFi might have been available and could be utilized to make and receive calls and send/receive text messages.

I ended my talk by explaining how users’ network experiences across the dimensions of Communication, Consumption and Creation would vary and, in some cases, improve.

After completing my talk, the Q&A with the audience included some spirited debate and a bit of skeptical questioning by a member of the Computer Science Faculty. I later received positive feedback from the Department of Computer Science Chairman, who had invited me to speak.

The networked experience 20 years after 9/11/2001

It is now twenty years after 9/11, and have I returned to the same question I asked myself in 2009 while preparing for my Tufts colloquium: “What would the networked user experience be for a catastrophic event should it occur this year?”.

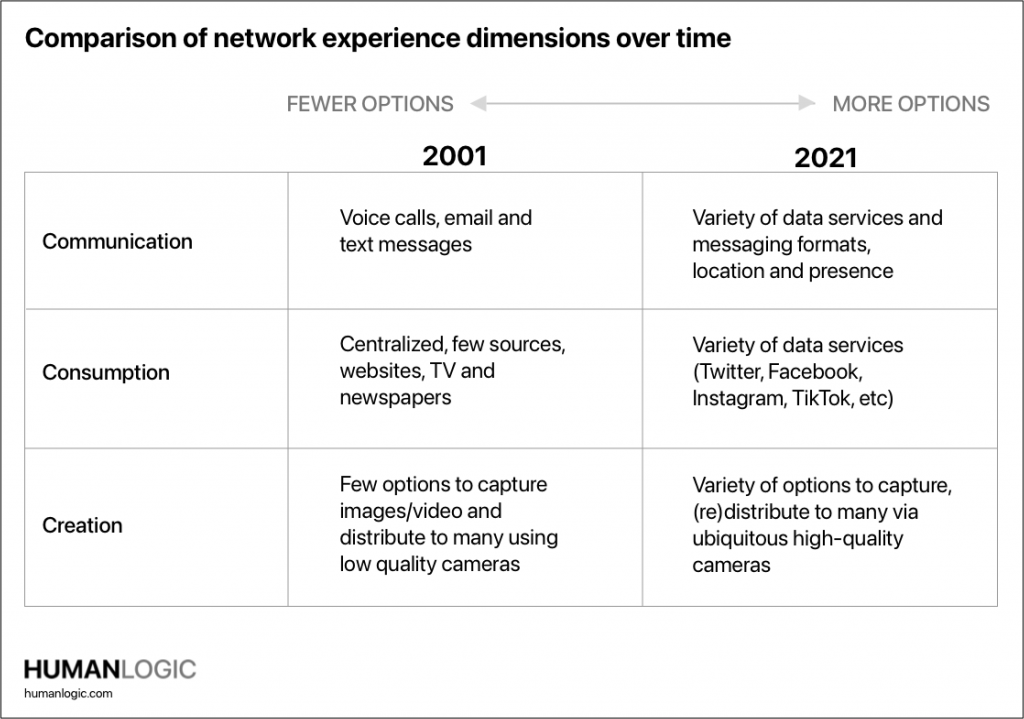

The table below compares the changes in networked user experiences between 2001 and 2021 against the three dimensions of Communication, Consumption and Creation that I discussed during my talk, followed by some of my current observations.

Connectivity has become richer but not more resilient and overall has not improved much nationally in the US. As such, the connection to the network for those involved in the September 11 event in NYC – both those individuals at the site and those trying to reach them – would continue to have cellular network outages.

Network congestion will always be a problem, especially when network capacity is reduced due to disaster conditions. In a disaster situation, you want the widest amount of minimal connectivity. You want to know if someone is OK through the weakest network connection possible, and you want to know their location. The resilience of US infrastructure has not improved since 2001, and this is evident in NYC in 2021 (see the effects recently of Hurricane Irma and, before that, Hurricane Sandy). Some messaging systems have added features to help support communication and allow users to mark themselves safe during crises (see Facebook’s Crisis Response feature as an example).

Internet use has replaced television news viewing. After 9/11, people used the Internet to supplement the information received from television (which was the preferred source of news). Those unable to view television often substituted their news consumption with Internet news. Now in 2021, users go to Twitter to learn about events, especially catastrophic ones.

Compared to 2001, in 2021, Max’s network experience during a catastrophic event would involve more connectivity throughout the day but remain vulnerable to data-sharing challenges. Considering the scenario of Max’s network experience in present-day 2021 during a catastrophic event, his day would begin with a subway ride during which he can read the news on his WiFi-enabled mobile phone instead of a paper newspaper. During the catastrophic event, Max’s location-aware smartphone – equipped with full data services and using a variety of networks – allows him to maintain communication with colleagues, friends and family throughout the event. Thus, even though his network connection may degrade, Max can still use text-based communication to reach out to family and friends.

As his day proceeds, decentralized and crowdsourced content distribution platforms such as Twitter and Facebook will allow Max to communicate his safety status during and after the attacks. In addition, in 2021, Max’s device will enable him to access news or social media updates as they are posted. Max’s phone can also capture high-resolution geolocated photos and video, though sharing them through the network connection may still be problematic.

In comparison to 2001, Max’s network connectivity in 2021 during a catastrophe enables a different user experience, one where asynchronous communication via data services is his first course of action – not attempting to make a synchronous voice call.

Conclusion

Each year just before September 11, I continue to think about this topic when I look up at sunny blue autumn skies. Networks and data access are critical enabling infrastructure and impact my work as a user experience designer. I encourage you to seek out your lens through which to consider the events of that day and think deeply about what has – and has not – changed since September 11, 2001.

About the author

Karen Donoghue is a Principal at HumanLogic.

Copyright 2021 Karen Donoghue, all rights reserved. Photo by NASA on Unsplash.

Additional reading

The Internet Under Crisis Conditions Learning from September 11 (2003)